Where Brod strove to clean Kafka up and foster a sense that he was, in Benjamin’s words, a “saintly, prophetic genius, whose purity places him at an elevated remove from the world,” this edition scuffs him up and returns him to earth, in an intimate manner that does no injury to our sense of his suffering, or his profound and original gifts. It’s an invaluable addition to Kafka’s oeuvre. The new volume, in a sensitive and briskly idiomatic translation by Ross Benjamin, offers revelation upon revelation. The sole previous English edition, with Brod’s edits, was issued in the late 1940s. Gone or disguised, too, were passages about Kafka’s visits to prostitutes.Ī new, unexpurgated and essential edition of Kafka’s diaries has finally been published in English, more than three decades after this complete text appeared in German. He excised passages that appear to express homoeroticism, for example. He pared away the flyspecks and stray hairs and human impulses. He made them seem more coherent than they were. Literature owes Brod a debt, even if, as John Updike wrote, Kafka would come to have this in common with Shakespeare: “Their reputations rest principally on texts they never approved or proofread.”īrod heavily buffed Kafka’s diaries before they saw print. As he did with so much of Kafka’s work, Brod, certain of his friend’s genius, published them anyway. Kafka did not intend for these diaries to be published he ordered Brod to burn them unread. Into them he stuffed all manner of things: letters, drafts of stories, aphorisms, dreams, snatches of observation. He kept his diaries from 1909 to 1923 they end not long before he died in obscurity, at 40, from tuberculosis. Do they matter? In Kafka’s case, one could argue that they do. Brod accidentally sprayed soda water all over Kafka, who laughed so hard that seltzer and grenadine shot out of his nose. In the spirit of Johnson’s anecdote about Heidegger, I’ve often recalled that, in his diaries, Kafka reports sitting in a bar in Prague with his friend Max Brod after they’d left an opera. He was, in novels and stories like “The Trial,” “The Metamorphosis” and “A Hunger Artist,” the visionary 20th-century distiller of guilt and shame, ill defined and thus quintessentially modern.

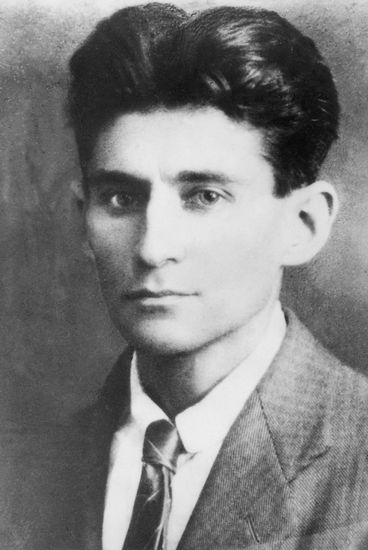

Like Heidegger, Franz Kafka (1883-1924) was not known for his lightness of spirit. It happened at a picnic in the Harz Mountains with Ernst Jünger, who “leaned over to pick up a sauerkraut and sausage roll, and his lederhosen split with a tremendous crack.” Martin Heidegger was recorded to have laughed only once, according to the historian Paul Johnson. THE DIARIES OF FRANZ KAFKA | Translated by Ross Benjamin

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)